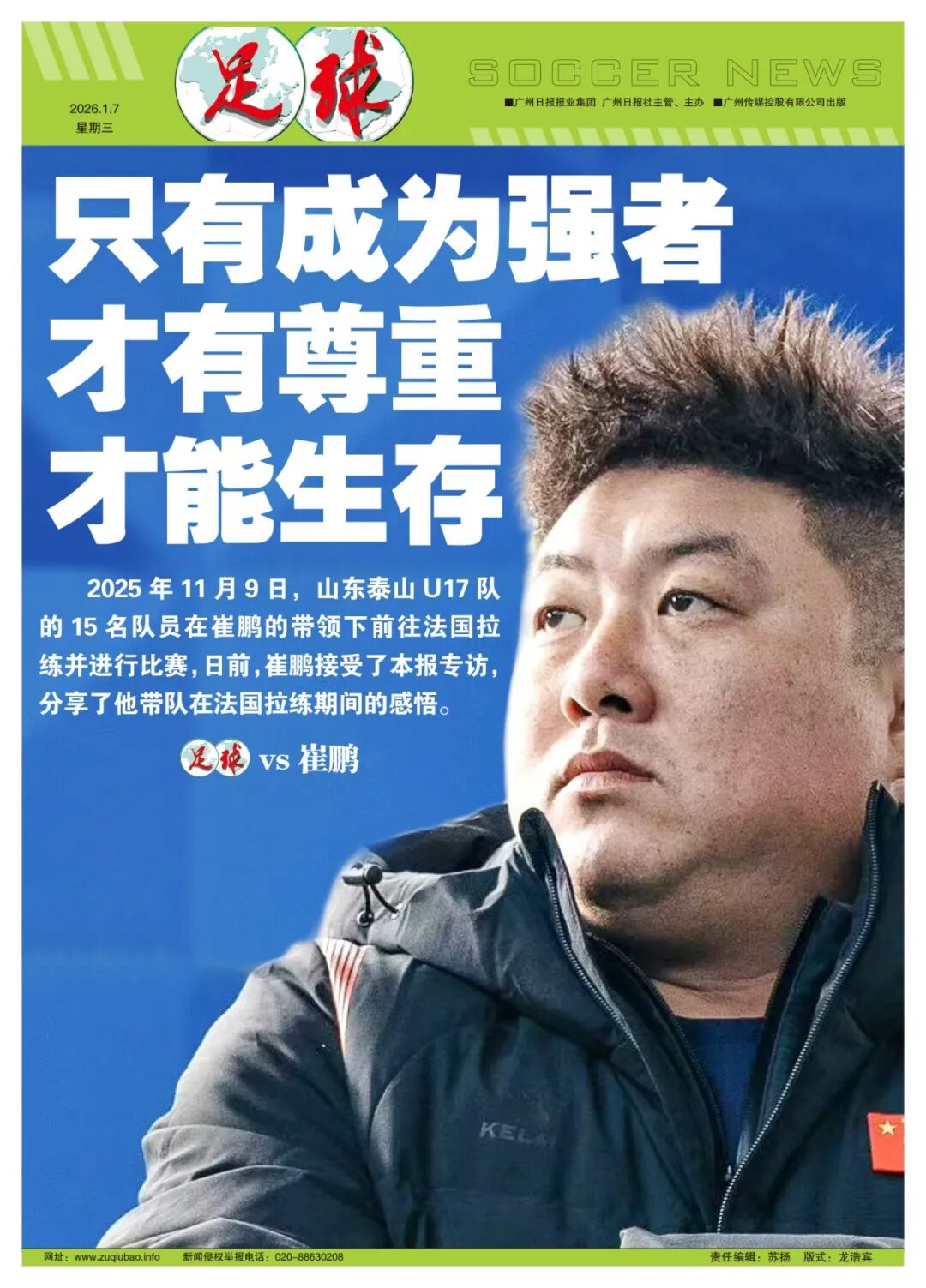

Taishan U17 Head Coach Cui Peng: Only by becoming strong can you earn respect and survive.

Reporter Chen Yong reports. Within the Taishan youth training squads, there is a story: other coaches often tell underperforming players, "If you don’t perform better, you’ll go train with Coach Cui!" This phrase is known as a "big weapon."

On November 9, 2025, fifteen players from the Shandong Taishan U17 team, led by Cui Peng, traveled to France for training and matches. So far, they have played five friendly games and participated in the first match of the French Hope Challenge, narrowly losing 1-2 to France’s Auxerre B team. Persisting with a philosophy of high intensity and fast pace, Cui Peng has had more encounters with French football. Recently, Cui Peng gave an exclusive interview to our paper, sharing his insights from the French training camp.

◆ "Football": After arriving in France, the team played several matches. How did things go?

Cui Peng: Up to now, we have played six matches in total, including five friendlies and one match in the French Hope Challenge.

The first match was against Auxerre U17 elite team, mainly to assess our strength. We played two halves totaling 40 minutes and won 1-0. Then we played two U18 teams from the Paris region, winning 14-1 and 10-1 respectively.

After three matches, the French side gave us high praise. Then the opponents got tougher: the fourth match was against Auxerre’s third team, which we lost 2-3. We led 2-0 at halftime, and although there were some controversies in the second half, it’s okay — I value the training benefit more. The fifth match was against Dijon from French League Two, a very strong opponent. We lost 3-5, but I was very satisfied with the players’ performance.

On December 9, we played against Auxerre B team as part of the French Hope Challenge, although this match did not count towards the standings. We lost 1-2. After the game, I released highlights, and many agreed that the intensity and pace were rarely seen in domestic youth matches.

◆ "Football": This overseas training gave you deeper insight into French football. What differences do you see in training between China and France?

Cui Peng: The Chinese Football Association recently conducted research and asked players how they felt about French training. The players said it was nothing special, which confused the researchers. Actually, the training levels in Chinese and French football are definitely very different, but our team’s training is similar to the French teams because since I started coaching, I have always emphasized confrontation and pace. Our training is both intense and voluminous: players may run up to 20,000 meters daily, with over 2,000 meters at high intensity. It’s very tough and hard to accept at first, but later they clearly feel their progress. So when they arrived in France, they felt the training wasn’t much different because that’s what we are used to. I also conducted a 12-minute run test after arrival; the players easily managed 3000 or 3200 meters. Of course, this is just our team’s situation. From my perspective, overall Chinese football training is far behind France’s.

I always stress confrontation and transitions, but in France, during real matches, players still aren’t used to it because of the opponents. For example, our players have good positioning; in China, opponents might not challenge aggressively, so we can calmly handle the ball. But in France, no matter how good your position is, if you stop, the opponent immediately challenges. There is no static football in France or Europe — everything must be dynamic. Even with good positioning, you have only a second to act: pass or quickly escape. If you stop, you face forced confrontation and maybe even a hard tackle.

We have many fast players like Li Xiang and Wang Yi, but opponents don’t fear speed alone. You must combine excellent ball control with speed to intimidate opponents. For example, the goal Li Xiang scored against Auxerre B was crucial because of his excellent ball control to shake off defenders, which is very important in real matches.

▲ Replay of Li Xiang’s goal (full highlights available on Cui Peng’s Douyin account “Mali Cui”).

◆"Football": How many matches have you played, and how do you compare the performances?

Cui Peng: The gap is quite big. We train with high self-expectations, but matches are different. The biggest difference for me between domestic and French matches is that in France, I don’t need to shout, but in China, I have to keep shouting.

It’s simple: domestically, players unconsciously slow down with the opponent’s intensity and pace, so I have to constantly urge them to increase confrontation and tempo. Even if we lead, they relax, so I have to shout or criticize them. But in France, I don’t need to do that; the match intensity and pace allow no slack. Our players maintain high focus and give 100% effort from start to finish.

This difference moved me deeply. Conversely, this may highlight the gap between Chinese football and advanced football nations, posing higher demands on all Chinese coaches.

The same applies to adult teams. Chinese professional football used to rely heavily on defensive parking-the-bus tactics. Last year, I watched the Chinese Super League, and the situation improved a lot; many relegation-threatened teams no longer park the bus. But overall, intensity and pace still have room for improvement. Intensity is okay, but transition pace is insufficient. I watched Ligue 1 matches in France: Auxerre is a relegation zone team, Lille is fourth in Ligue 1. Auxerre played aggressively all game with high pressure, confrontation, and transitions, losing narrowly 3-4, showing only a slight difference in individual ability.

In the 14-1 win against a Paris regional team, the score gap was huge. If the opponent had retreated, we might have struggled to score so many goals, but they never held back and played as usual. This left a deep impression on me. Conversely, in the matches against Dijon and Auxerre B, we were clearly weaker but still pressed aggressively and fought hard until the end.

◆ "Football": What are the differences in combining training and matches between Chinese and French football?

Cui Peng: After finishing the Hope Challenge, I conducted two weeks of training without matches. I needed to fully absorb the lessons from previous games during training.

In China, we have many matches, but the progressive model of "training–match–training–match" is not well established. Simply put: first, many matches are tournament-style with tight schedules, so the match content cannot be integrated into training; after the tournament ends, the training content cannot be tested in matches. Second, throughout the year, we don’t have many truly high-quality matches that feel valuable. The combination of training and matches should be high-quality training combined with high-quality matches. If both are low quality, then training and matches only make things worse.

I communicated with French coaches; one said our team was better than expected. I asked for advice; he said our pace is very good but our defense lacks systematic organization. Our transition from attack to defense is well done because it relates closely to tactical discipline and mentality. Transition from defense to attack also relates to these but is more tactical. We lack efficient tactical organization in defense-to-attack transitions, which is an area to improve.

◆ "Football": Is there a clear difference in player selection between China and France?

Cui Peng: I have discussed this with French colleagues. In my view, French and European football always prioritize physical qualities as the core criterion for selection.

In the first Hope Challenge match, the opponent had eight black players, two mixed-race players, and only one white player. One player was very fast and sharp offensively, posing a big threat. However, the coach’s evaluation was that he had obvious weaknesses and was afraid of confrontation. I also compared Auxerre B and Auxerre third team: B team players clearly had better physical attributes.

In France or Europe, there are players with average physicality but exceptional talent, but this is not common. Generally, you must first have outstanding physical qualities, which determine if you can reach a high level because it affects your ability to confront and adapt to pace. In other words, the current global trend of strong confrontation and fast pace means physicality is the primary core.

Even within Taishan youth squads, some players have good technique, awareness, and passing skills, but in my system emphasizing confrontation and pace, unless a player quickly improves physical fitness and adapts to match intensity and pace, I probably won’t choose him as a starter. Even if he starts, it would be against weaker teams to use his strengths; against stronger opponents, he would likely be a substitute. I would decide when and where to use him depending on the match. Also tactically, starters must have enough adaptability, excellent stamina, confrontation, and defensive abilities; otherwise, I must change formation or use a midfielder role to maximize the player’s strengths and avoid weaknesses.

From my perspective, European selection standards generally require excellent physicality as a foundation, then better technical skills and tactical awareness.

Physicality has innate factors; many players have excellent natural physical qualities. But physicality can also be improved through hard work: while others play on their phones, you train core strength; while others watch TV, you improve fitness. Naturally, your physicality improves.

◆ "Football": How do you evaluate the team’s performance?

Cui Peng: I am very satisfied. Because of the training foundation, when we arrived in France, our players adapted well to the intensity and pace. Objectively, we still have physical gaps, especially since most matches were against older teams — small players versus bigger ones, with greater physical differences. But we dared to press high and transition quickly throughout. When physically behind, we compensated with running, and our pressing created many opportunities.

In France, although we are just Taishan’s youth team, we represent Taishan, and in fact, we represent Chinese football because opponents will say, "Let’s see how this Chinese team plays." I want to prove something for Chinese football. After our 1-2 loss, I reflected on whether we play to win or to find better ways on the right path. But one thing is clear: we must never back down. On the field, it’s life or death, real combat with no retreat or cowardice allowed.

Now, after 50 days in France and six matches, I am proud of them. They showed no fear or hesitation on the pitch. If everyone acted like this, I believe no one would criticize Chinese football.

I came to Shandong in 1998. People say it’s the land of Confucius and Mencius, a place of respect. But what is respect? If you are trampled on, is that respect? If you always respect opponents on the field, you lose dignity both on and off the pitch. Only the strong earn respect and survive. For example, in domestic youth matches, players leisurely finish games, then bow to thank referees and opponents. That gains no respect. Of course, football requires manners and etiquette, but its true essence is fighting.

Fans ask me what will happen to this team when they return to China. The environment may differ, but since they deeply experienced European football, they must set higher standards for themselves when back home.

◆ "Football": Going abroad is a key way to improve football skills. What is your view on Chinese players going overseas?

Cui Peng: I think when we go abroad, we must truly understand the reality of European football and prepare thoroughly.

The fundamental difference between European and Chinese football is survival mode. European football follows jungle law; don’t expect the care and protection you get in Chinese youth training. Many kids get lost here because in China they have school leaders, coaches, team managers, and parents caring for them. In Europe, coaches only focus on training and matches; they won’t help you in your free time or nag about details, nor encourage you when you face setbacks or lose motivation. They only watch your training and match performance. Of course, you can pay for extra training, but that costs money. Also, language barriers and lifestyle adaptation cause many problems.

This natural elimination jungle law in European football leaves no room for warmth. Out of ten thousand kids playing football, maybe only one becomes a top league player. There is no excess care. Everything depends on yourself, fighting hard to win your survival chance.

European football has no obligation to accept you; you must work harder to become strong, earning respect and recognition. So we must be fully mentally prepared for going abroad. Fortunately, now more Chinese-funded clubs provide conveniences, which is a blessing for Chinese football. But ultimately, your survival and respect depend on your effort, resilience, and ability.

During training, French coaches asked why our training volume and intensity are so high. I said if we don’t train hard, the gap with you will only widen. Coming to France this time, I feel lucky to observe and reflect closely. I also wrote a report to share these realities with China.

◆"Football": How does your growth from professional player to coach benefit youth training?

Cui Peng: The transition from player to coach has given me many insights. Looking back, I have many regrets. When Magath coached me, his impact was huge. At first, I thought he was extreme, but after a while, I lost a lot of weight. His influence extended beyond my playing days and even more into coaching.

As a youth coach, my principle is to emphasize confrontation and pace, applying this in matches and training with full intensity and volume. Other coaches often tell underperforming players, "If you don’t improve, you’ll have to train with Coach Cui!"

Many players resisted me at first, but later realized they were improving. For example, Duan Feida is an excellent center-back, 1.89 meters tall, with great potential. At first, he was reluctant to train strength, but now he feels his progress and works hard to improve.

I am also changing. I live and eat with them, care about their lives and even emotional wellbeing. I don’t want the mistakes I or other players made to repeat in them. I tell them we rely on each other. After arriving in France, I paid for Chinese meals for them because we truly depend on each other, improving together through this bond.

Before the Hope Challenge, I told the players I can’t say they only have me in their lives, but now I only have them in mine. Why not join hands to create a better tomorrow? They performed very well. After the competition, I gave them a break and took them sightseeing in Paris. Sometimes I worry that if I stop coaching this team, they might revert to old lax habits. But ultimately, everyone is responsible for themselves. As a coach, I have no regrets — I only provide the best philosophy, training, and matches.

Wonderfulshortvideo

CR7 was really going through it 🤣🏆

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

App

App